Tags

Everybody says that the second you get off the plane in India, you know you’re somewhere different. The heat, the air. You feel it. My first time in India was my first time in Asia and the first 24 hours was an amazing joyous culture shock.

First I got picked up from the Delhi airport in a car sent by my news station. My friend and editor in chief Rohit made sure I landed softly. In fact I was staying at his home for the first few weeks of my stay. I owe him so much!

The cab ride from the airport to his home in Vasant Kunj was unbelievable. I looked wide-eyed at everything I saw, stunned. You see people. People around fires in the streets. The space between Pearson to downtown Toronto is filled with fields, parking lots, cars, strip malls, empty expanses. There, there’s stuff and the character and density shocked me.

I reached his home by midnight, and by 4am we woke up early to beat traffic en route to the Jim Corbett Tiger reserve, where Rohit owned land on which he was building a facility for researchers. The drive there was unbelievable. Emerald rice fields, banyan trees shocked me and evoked remote jungles. It was the jungle. It’s hard to state how different everything looks and feels because it was hard to process at the time. Looking out a car window was a constant rush, I couldn’t look away.

On the drive we stopped to wait at a train crossing. While our jeep blared Justin Bieber, Tanya’s music, Rohit’s daughter, a gentleman stood beside me with his cow, which suddenly started urinating in a thick stream right all over his ankles and feet. The guy didn’t move a muscle. I could hear it but it’s like he didn’t even feel it, or simply didn’t care. Hearing Bieber play while watching that felt like straddling two very different worlds.

The natural landscape was awe inspiring. We drove through dry river beds, where the traffic was quite different than I was accustomed to.

We drove through small Muslim villages on the way to Uttarakhand and even seeing things that would be common later, like tea stalls or whatever, blew my mind.

At the tiger reserve, men with very simple tools were building. Ladders of bamboo. No power tools, no electricity, I don’t think. Language barriers prevented communication. But they had a kind of small tree fort where, from that height their phones could get some reception and up there was a solar charging station. This level of old school resourcefulness for modern technology was new to me and impressed me. The funny thing is, unlike me, these humble Uttarakhand builders had data plans on their phones–I hated smartphones, still do, and never wanted one. I only got a data plan for my first time in the upcoming months, in Delhi in 2016.

The charging station and my bed for the evening

But even the construction site was nothing like it would have been in Toronto. It was less a construction site than just…people building. No signs explaining the project’s scope, approvals displayed for inspectors.

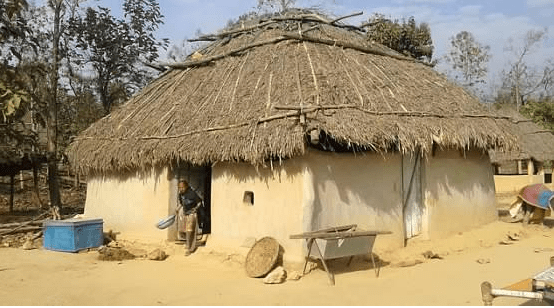

We went on a “safari,” ie a drive through the forest looking for tigers. We didn’t see any but the possibility was real, if remote, and that alone was exciting. Nearby some nomads lived, gypsies. Most of them were in the mountains then, except for one woman who spoke to Rohit and seemed friendly. They lived just a few minutes walk away.

The gypsy’s home

I had a bottle of single malt I picked up from the duty free. To add, Rohit said, “Oh, you like hash, don’t you?” Yes, I’ve been known to inhale. So he muttered something in Hindi, which to me sounded not only like a language I couldn’t understand, but like a language nobody could understand. I realized, I had never heard it before. Two seconds later a gentleman builder handed us a big hash joint. Potent, too!

Now I grasp that a bottle of Indian booze, say Old Monk rum, went for like 300 rupees, or roughly $6 Canadian. Scotch is a luxury anywhere, even duty-free, but there, imported to India, it’s coded as “Western” and the subtext of the luxury is on a higher plane.

That night I played some Bowie tunes on my travel guitar by the fire, passed the Laphroaig around, smoked some hash which I was told simply grows everywhere there like weeds. I hope the labourers liked my songs. I think they did.

It was a very cold February evening sleeping on a charpoy outdoors under an open-sided thatch hut, all snug under very thick blankets. The night sky was not only extremely brilliant and crystal clear but the stars even seemed to be positioned differently from the stars I normally saw. Imagine how strange it is to look at the countless stars in the sky and think, “these aren’t the stars I’m used to, every star has changed its position.” That I could be so far away from home that even the heavens looked and was different transcended cultural differences.

A family of elephants sometimes pass through that area, but sadly they weren’t there the next morning. Still, the possibility excited me and made me feel like I was somewhere special. We woke up at probably 4 or 5 am to beat traffic back into Delhi to witness a creature even rarer around those parts than any elephant or tiger: the premier and leader of Ontario’s Liberal party, Kathleen Wynne.

Rohit interviewed her at the Taj hotel, a posh 5-star hotel in South Delhi. I showered quickly and tried to trim my beard to look more appropriate because we weren’t in the jungle anymore, but of course the voltage was wrong and my trimmer got fried. No worries: Suhail, Rohit’s assistant, a friendly young man who I was told could shimmy up a coconut tree and split a coconut open with his bare hands, was also trained to be a barber and trimmed my beard with a comb and scissors. We’d become buds despite not really being able to talk to each other too much.

Before the interview, sitting there in the Taj, I was chewing the shit with one of Kathleen Wynee’s aide, a Toronto guy in her retinue. We talked about restaurants on Dupont Street, probably tacos at Playa Cabana or some Anthony Rose spots. Going to about the other end of the world only to come right back that quickly was super weird. Whiplash.

In hindsight, I was in a class bubble that was very hard to perceive at the time because I had in fact travelled very far and things around me were in fact very different.

Landing in India, you think you’re in “India,” and of course I was, but more specifically I was based in New Delhi, or just outside Delhi in Film City, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, working for Zee Media to launch and work for the country’s first-ever English language news TV station and website, World Is One News. WION.

I might have seen Muslim villagers in the foothills of the Himalayas, a gypsy woman, and Uttarakhand labourers after driving through a dry river to get to a teak jungle, but I couldn’t talk to them. The people in India I could talk to were much less exotic.

Such were my first 24 hours or so in India.