I used to be very drawn to guitarists playing music that I, a guitar player, couldn’t imagine myself ever being able to play. Look what Django can do! It was a physical feat, a triumph of dexterity. Of course the physical feat was very much connected to the sound: Watching somebody move their fingers how their solos required but without a guitar in their hands—essentially, air guitar—would have meant nothing to me. I’ve been wrestling lately with the relationship between the physical part of music, what’s required to play it, and how music actually sounds, how they’re connected and how to feel about it.

I think the best way to think about it is to create categories along these lines. Simple-great and hard-great on one hand, simple-sucks and hard-sucks on the other.

In simple-great I’d put Neil Young and David Gilmour of Pink Floyd. Neil gets the most out of GCD songs imaginable. He does use some odd tunings and unusual chords, too, and his voice and songs are just so beautiful and singular. He’s a musical god! I’ve spent years playing his songs on guitar and really love him, but there are much more complicated players out there. Neil has feel. Priceless feel. If you practice, you can sound a bit like Neil. Maybe get 80-90% of the way there. But the voice, the guitar sound…Neil is alone. David Gilmour’s solos are mostly pentatonic stuff, but they’re just so, so perfect. There’s a logic to them and you recognize his sound right away. They’re both very accomplished musicians and I don’t mean to give them a back-handed compliment! But to me, they’re both simple-excellent players. Emphasis on the excellent, more than the simple.

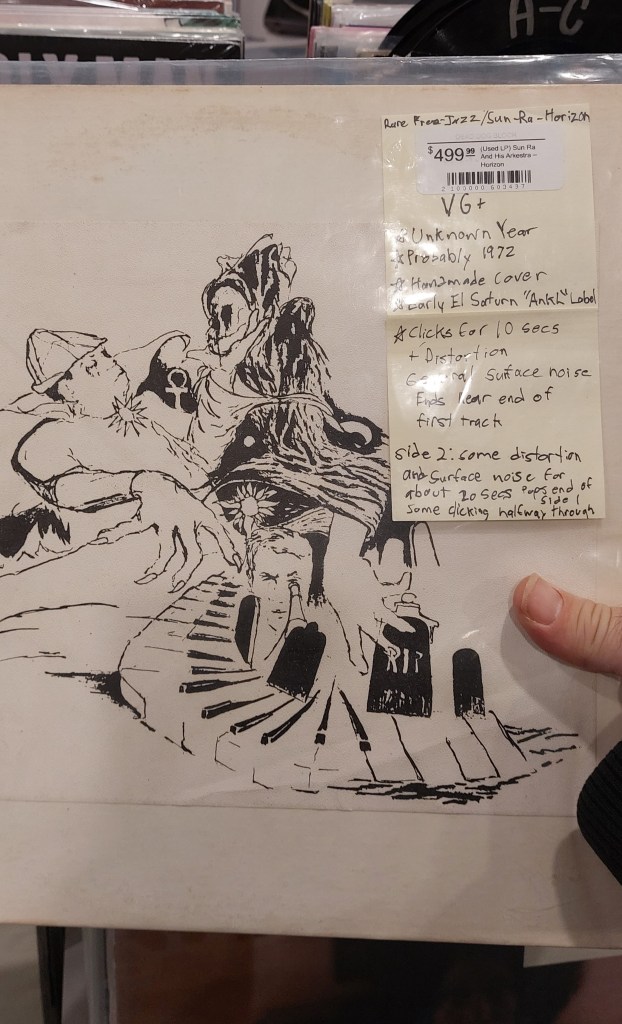

In complex-great I’d put Jerry Garcia, Sun Ra, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane. Musicians like that who use various scales and modes over fast, sophisticated chord changes. You need to know your instrument inside-out to play like them, not just have dexterity or a great ear. Improvisers have a very different relationship to their instruments than people who compose music and play written music at their concerts or in the studio.

Playing like Charlie Parker is like solving a Rubix cube while dancing. He was bouncing in impossibly new, daring, inventive ways within his music’s tight constraints. His feel and technique are both top notch. All these guys have endless technique and feel.

The point isn’t to put one type of player over another; if you’re excellent, it doesn’t matter whether it’s “simple” or “hard.” More a question of what mood you’re in, as a listener. But I’ve asked myself, what happens when a musician has been a virtuoso for decades and for them a “difficult” musical passage is just as easy to play as an easy one? How does their proficiency on the instrument affect what they want to play, and how we hear their music?

To help understand the kind of dynamic I’m talking about, imagine listening to music inputted into a computer, rather than played manually by musicians: would you find the faster, “harder” passages more enjoyable than the slower, “easier” ones? When the physicality of playing music is removed from the equation, does our judgement and appreciation for its sound change?

On some level, we don’t trust an artist’s authority unless they dazzle us by doing something we can’t. In musical terms, this means playing fast, complicated passages. People wouldn’t have taken Picasso’s abstract stuff as seriously if he hadn’t demonstrated he could paint like the Renaissance masters.

Along the same lines, free jazz players squawking on their horns would be dismissed outright by many as charlatans or lunatics if they hadn’t demonstrated that they could play conventional jazz too. Many still are.

For years I was floored by the harmonic knowledge and manual dexterity required to play guitar like Lenny Breau and Joe Pass, guys who simultaneously play chords, basslines and melody as a solo act. Sometimes they play all three at once, or two, or one, alternating between these roles smoothly. It’s incredible to do! You need a commanding knowledge of music theory and probably no amount of practicing will let me play like this.

But who cares? Today I listen to it and think to myself, yes it’s still beautiful and impressive, but get some friends! Find buddies to play instruments so you don’t need to do the bass, chords, and melody all alone! Joe Pass sounded better on For Django where he had accompaniment and could just solo and leave the rhythm to his band. Breau to me sounds better with less on his plate, too. They’re freed up.

Was I listening to just the sounds they were playing, or were their physical accomplishments (and theoretical knowledge the playing rested on) seeping into what I heard, influencing it?

You can have total command of your instrument and know all there is to know about music theory, but that doesn’t make your music great. Some players play a million notes a second and don’t really say anthing.

On the flip side, the Beatles couldn’t read music. Neither could Jimi Hendrix. The Band relied on Garth Hudson for deep music theory stuff, just like P Funk relied on Bernie Worrell. But music is a results-based medium: if it sounds good, it’s good.

Proficiency and knowledge are just tools. Not knowing theory, or lacking notable skill on your instrument, can be major a limitation, but not always! Some musicians take power chords really, really far. Punk can be about raw visceral power and attitude on stage or on record, more than elaborate solos. Just like bad music isn’t made better because the musician playing it knows all the scales and plays proficiently, good music isn’t bad because the musician playing it doesn’t know about the cycle of fifths.

There’s a difference between how sophisticated music is and how good it is. I’ve stopped thinking about it this way and feel better for it. It may sound odd, but sometimes complexity and simplicity are fused together. Sun Ra would ask Arkestra musicians to remember what it felt like when they first picked up their instrument, to play with some of that freshness, simplicity. The point is to transcend musical knowledge for self-expression.

I try to think critically now about music only to widen and deepen my appreciation for as much music as I can, whatever I happen to be listening to. The point isn’t to build up theories that proclaim a musician good or bad based on how hard it is to play or grasp.

Some players who shred have nothing to say. It’s not even clear that “hard” passages are actually harder to play. Playing slowly can be harder than playing quickly, actually. There’s less room to hide mistakes and every little movement of your finger affects the tone. Every bend, every shake and vibrato. The phrasing really stands out more when there’s more space for the sound to breathe.

The binary between simple-hard isn’t really a good criteria for evaluating music. When musicians are spiritually deep and have total command of their instrument and music theory, you’re probably in very good hands! But these are just tools.

Sometimes very good musicians who lack formal training are insecure about their gaps in knowledge. They shouldn’t be! If you can play, you can play. If it sounds good, it’s good. I hope conceiving of music as good/bad not simple/hard frees up musicians and anyone listening to music from the burden of needing to prove themselves or justify their preferences and musical tastes.

I’m not exactly saying “let people like stuff”! I’m describing how I listen and evaluate music for myself. I’m not here to scold or praise anybody for what they like; the point is for each person to widen and deepen their own musical appreciation by spending more time to consider music they may have dismissed at first glance as being too simple or, on the flip side, too weird or hard or out there.

There’s a world of difference between the Sun Ra Arkestra and Britney Spears, musically speaking, but they’re both valid and cool, even if I can tell you which of the two I listen to more.