Tags

Jeff Halperin, Lauryn Hill, Marvin Gaye, Mats Sundin, Nabokov, Parliament Funkadelic, Proust, Sun Ra

When I was young my father explained the “error of parallax” to me and today, though my memory is total garbage, that stuck with me for some reason. The error of parallax occurs when you observe something from a skewed angle and misread it accordingly. The simplest example is to imagine yourself in the passenger seat of a car, unable to gauge the speedometer accurately because you’re looking at it from an angle, not from the driver’s seat.

So that’s how parallax works in terms of physical space. I’ve been intrigued lately about how this same bias works in terms of time. When are you really looking at a moment, square and dead on? During it, or some time after?

Adults know how weird it is returning to places you spent time as a kid which seem much smaller than they used to. Physically, you were smaller too. These places were bigger, relative to your size then. I think as a person grows physically, maybe the world around them shrinks.

But also things take on mythical proportions when you’re young, and the passage of time evens this out. That’s why pro athletes seem not just like adults when you’re a kid, but giants. Men. When I was 13, nobody could have been older or more of an adult than Mats Sundin. He was 26. Now, I’m 41.

This is one way I think parallax works in terms of time. But there are other similar distortions too on different scales.

It’s common for every generation to think they had it hard, they were hardcore, and today’s contemporary whippersnappers are soft. We used to walk five kilometres to school in snow this high. There’s always some reason why adults had it rough and kids today are soft. Today’s soft kids will have had it hard as youth, but only once they grow up and see a new crop of young indulged kids.

There’s always some problem society gets fixated on solving, and people are soft because back in my day nobody cared about it. Today we have mental health diagnoses for problems nobody knew existed. This language gives us a framework for understanding behaviour previous generations lacked. Frankly, sometimes I think pseudo-psychology gets tossed around casually, and people sling therapy language around willy nilly, but by and large we understand that conditions people have can sometimes account for behaviour that would otherwise be difficult to us to understand.

This affects how people see a past time and their own. Everybody in their 40s today lived through the 80s, but not as adults. Their perception about what the 80s or 90s were like is no doubt shaped by their age. Is their sense of time skewed by their age? What exactly is the right age to perceive an era?

Today’s adults don’t know what it’s like to live in 2026 as a child. That’s how parallax works in terms of time. It’s unavoidable.

That’s why all those fiery op-eds about what Millennials or Gen-Z or Gen-X are like seem silly to me. People are always the same. Technology changes, economic conditions change, and people adjust to this matrix of things accordingly.

Baby Boomers shat on social media when it came out, believing you had to be a vapid idiot to use it. Now it’s a cliché that they’re the first to believe the most outlandishly fake crap posted on Facebook. They were never above using social media, it just wasn’t aimed at adults initially. (Originally, you needed to have a university email to use Facebook). People didn’t use a social media platform invented in 2004 back in the 1960s and 70s for obvious reasons.

With physical space, it’s easy to understand what a straight-ahead perspective is and look at something dead on. With time, this is much less clear.

Sometimes, you don’t understand just what you’re looking at until you get a broader context than is immediately apparent. Maybe you need time to process what’s going on. That’s what the phrase “hindsight is 20-20” means. It suggests the moment itself isn’t the best time to accurately grasp what’s going on.

That’s why parallax is different for time. Novelists love thinking about this kind of stuff. This is Proust’s subject, and he called his famous novel, In Search of Lost Time. As Nabokov elegantly describes it, “it’s a treasure hunt where the treasure is time and the hiding place is the past.”

In a way, the idea of involuntary memory, where one sudden whiff of a tea biscuit can summon core memories long thought buried, contradicts the idea of hindsight being 20-20. It’s not hindsight that makes the memories come alive, but olfactory stimulation. ie, a smell. Then again, eye witnesses for crimes often remember things they witnessed very recently very incorrectly. Memory and time and perception are funny things!

People talk about the relativity of time, how it can move quickly or slowly depending on what’s going on. One new theory I semi-believe is that everybody is every age at once. Seniors carry with them many things from childhood, and have carried their childhood with them constantly, every day of their life. On the flipside, the way you treat a child today is something that can stick with them for decades, so in a way, you’re interacting with that future self too.

It’s not that they’re literally every age at once, it’s that time is only alive in memory. Sometimes people make up a memory, or misremember something that they genuinely think is real.

One funny thing people post online about macro time, epochs, is that we currently live closer to Cleopatra’s age than Cleopatra was to the Pharaoh Cheops, of Cairo’s Great Pyramid fame, Cheops. That’s how long the Egyptian dynasty was.

On the flip side of this grander scale, in music, I’ve become a much keener appreciation of rhythm. Time can be measured in millennia or measures, bars. Everything is on the one. Some jazz and hip hop beats have a lazy behind-the-beat feel I just love, a type of drawl. A hiccup. The P Funk album Funkentelechy Versus the Placebo Syndrome takes part of its name from the Greek word, entelechy, which is concerned with a being achieving its fullest potential. The way I understand it, P Funk is trying to ask the listener what the state of their funk is now, in the moment that just elapsed, and the next one, and the one after that. Are you realizing your full funk, now, and in the constant now-ness? That’s where the Funk is. It’s on the one, and it’s now. That’s one micro perspective on music I think is cool.

Some musical ideas I’ve had consider time on a small and larger scale at the same time. There are Sun Ra records where the A and B sides are from completely different sessions, perhaps years apart. Maybe this was done unintentionally, as they pressed their own albums and recorded their own music constantly and could have simply lost track of what session was what. Their discography is notoriously challenging. I prefer to think of it as Ra playing with time in a micro and macro sense. Side A is from 1962, side B from the 70s. Greatest Hits albums arguably do the same thing.

What does it mean to have an “old soul”? Usually it’s when a young precocious person likes older, more cultivated art, or seems philosophical beyond their years. But even the way we understand art is influenced by time in a major way. For one thing, older books, movies, or songs have had years of scrutiny, and if people still love them after decades, that’s a test new art can’t possibly get to take, let alone pass. It might pass that test later, but not today.

It’s not just that grandparents aren’t impressed by the music their grandchildren listen to. Louis Armstrong had nothing great to say about bebop, and today, jazz standards written by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie are a bedrock part of the jazz Canon.

It’s possible to get swept up by music because it’s current, because it responds to current events or the current moment, but this currentness can also obscure perceptions. Sometimes, topical art speaks to a moment, but isn’t remembered much after that current moment passes. Even that word, current, is great because it invokes water moving in this or that direction, just like the passage of time.

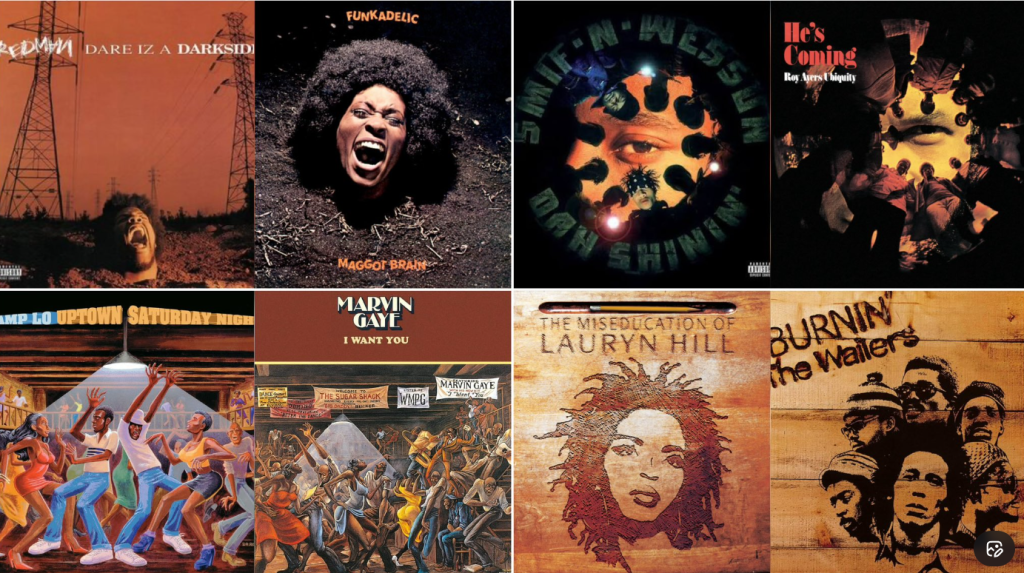

I saw a post on twitter recently, where someone was lamenting how today’s youth are nostalgic for the 90s, which have passed. Give it up, they’re gone! That was the message. In response, a gentleman I follow posted pictures of 90s albums harkening back to music from the 70s. The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill took her cover from Bob Marley’s Burnin’. Marvin Gaye’s 1976 album I Want You was the basis for Camp Lo’s Uptown Saturday Night.

Being nostalgic for a time period you didn’t live in is timeless behaviour, if you will. Musicians have always mined the past for sounds and feels, because what else can a musician know but music they’ve heard before? Norm Macdonald made the joke, that “this is a picture of me when I was younger” should be followed by “every picture of you is a picture of you when you were younger.”

Musicians can’t be influenced by music that hasn’t happened yet, so the past is the only place to look. Novelists, same thing. It’s a question of how far back you go, and in which directions. Any new art has something of the old in it too, and this is how time moves in two directions at once.

Parallax for space rightly assumes that there is one central point from which a perspective is centred, the correct one to look and measure from. This doesn’t exist for time, or if it does, it’s not straightforward. In a sense, we live in every time that has ever occurred, even if the past is buried somewhere and yet to rise, awaiting for whatever will excavate or summon it.