Tags

2016 US elections, Demonetization, India, Malana, Pushkar, travel, trump, WION

You already know the results of the 2016 US election but I promise you, my perspective on it was entirely different. Most North Americans don’t know what “demonetization” in India even was, which began that very night. These are really two interconnected stories, both of which were shocking.

In 2016, I was the lone North American on the WION web desk, so it fell to me to write about the US election for the site. The week leading up to the election, I volunteered to work the graveyard shift, 10pm-7am, to be in synch with North American time. 11pm Delhi time is 9:30am in North America. That way, the website would have news as it unfolded.

The evening of the US election, the entire team volunteered to stay up all night on the graveyard shift. As major as that US election was, that wasn’t the major news story of the evening: at around 9pm, without any warning, the Modi government announced that 87% of the paper bills in circulation would suddenly no longer be accepted as payment, starting at midnight. This was known as “demonetization.”

People’s cash wasn’t suddenly valueless, but they had to swap their old 500 ($10 Cdn, roughly) and 1,000 rupee notes ($20) to their bank, and if the total money was over a certain amount, explain how they got them. But people couldn’t use their old bills to make purchases.The government issued new 500 notes and phased out the 1,000 rupee bill altogether. 10, 20, 50, and 100 rupee notes would still be acceptable.

Nobody in a country of 1.3 billion people saw this coming! People panicked. A lot. Whatever the rules were for what to do next, they weren’t immediately clear to all. The justifications for such a massive, drastic policy also kept shifting in the days to come.

First, demonetization was to crack down on terrorism. Supposedly, terrorists would have all these old bills they couldn’t launder, couldn’t explain to a bank how they got them. Next, it became about cracking down on black money and tax avoidance. Shady industrialists were supposedly the target.

Then it became about transitioning people into using the banking system and digital payments. When Big Business comes to India for its enormous middle-class, they expected people to pay via tap, rather than submit crumpled rupee notes. Along these lines, in addition to a new 500 rupee bill, India issued a brand new note of a higher denomination, 2,000 rupees ($40 Canadian).

The web team’s all-nighter to cover the US election was thrown for a loop, as this mammoth national story overtook it. That wasn’t the last surprise of the evening.

So maybe around 6am, my editor and good buddy Tathagata and I went down to the caf to get the team some snacks. Of course there was a problem; we had invalid bills! Right.

We had been covering demonetization for hours, but what was happening didn’t really hit until we went to pay for something and it affected us. I scrounged up my last hundred rupee notes to buy some egg bhuji, shaking my head. Suddenly I was living in a very different world.

Then minutes later I got upstairs and they announced Trump won the election. Suddenly I was living in a very different world. Holy shit. This is 2026 now, we’ve all lived through some truly shocking events, but right then, I’ve never had the rug pulled out from under me like that. It was a double whammy, back to back shots, each punch seismic.

Colleagues wondered why I looked so devastated. I wasn’t crying, but I had been following Trump closely from the start of his campaign, and frankly you didn’t need to to know the world would never be the same again. Anybody could tell Trump was a cerified fascist just from the way he decorated his living room.

I couldn’t take it and left the building. I really couldn’t be there anymore, writing stories like things were normal. It had been the end of a very long week and I was heading into a couple days off and decided I absolutely needed to take them now.

Grim news aside, working from 5am-2pm in one rotation, then 2-11pm, only to work the graveyard shift will turn anybody’s circadian rhythm upside down at the best of times, especially because my friends and family back in Canada were 10.5 hours behind me at any given moment, adding another dimension of disorientation.

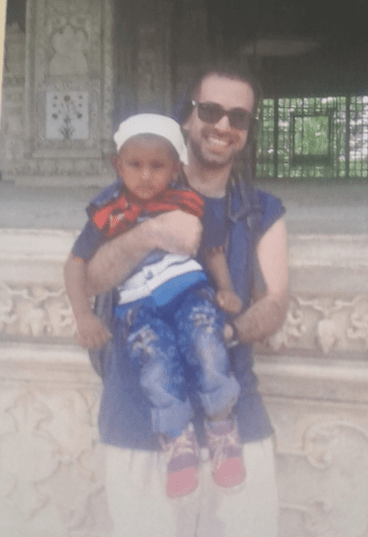

I needed to get away. As it happened, I had recently gone out with a sweet girl I met on Tinder who told me she also wanted to get away for a bit, to Ajmer and Pushkar, Rajasthan. It was the Camel Fair, an enormous annual festival where people from across India assemble with their livestock and camel decorations and much else. It was settled, we’d go together.

One practical question first though was, how to get money? India relied overwhelmingly on cash, which meant vendors couldn’t necessarily accept debit or credit card. I only had so much cash and getting more was the question of the day.

In the first days of demonetization, everybody was desperate for cash. No joke, people lined up for days at ATMs, there were reports of some people even dying right there in line because they had medical problems but couldn’t leave their spot–they needed money. It was desperate. You might wait for hours for an ATM to get cash, but the government limited how much you could withdraw at a time to 2,000 rupees. When an ATM did finally get cash, in places, the rush was like those old clips of Black Friday at the mall.

An Uber might be way more expensive than an auto rickshaw, but you could pay through the app, not cash. It was worth spending more money if it meant keeping cash on hand for essentials that required cash. This was a privileged position, a very rarified adjustment compared to what other people in India faced, but it’s what I was navigating.

Anyway, Gopika told me she was starting to kind of date somebody and was it OK if he came on the trip too? Sure, I told her I didn’t care. We had been on one date I enjoyed, but that was fine with me. When you’re working abroad it’s nice to hang with non-colleagues and get away from office gossip and shop talk, especially then. Companionship aside, it’s also nice to travel with people who speak the language and know the deal.

But when that dude found out I was coming too, he didn’t want to anymore, so in the end it was just the two of us.

First Escape: Rajasthan–Ajmer, Pushkar

I met her in Gurgaon, (“Gurugram” now, since Modi de-Islamified the names of Indian cities,) and we took an overnight bus to Ajmer. Walking around that place in the morning was wild! When you touch down in India, you equate the first place you land as “India” because it’s your first exposure to the country, but India’s impossibly vast, places are radically different from each other, and they’re all “India.”

Rajasthan was so arid, the animals felt closer in the streets and different. I didn’t realize that I had a grasp on what kind of cows Delhi had until I saw the strangeness of other cows and bulls here, and one really gnarly wild boar just walking around. It was November, so it wasn’t hot out. Winters in India are what summers are here, the pleasant time to be outside.

I also laughed seeing a dude wearing a “Bury Me In My Ones” t-shirt with a Nike Swoosh, which a curated vintage store here could sell for $100+. It’s hard to explain this and I don’t mean to sound judgey, but I sensed this fella was not a hip dude aware that he was rocking vintage 90s streetwear. I doubted that he knew what Air Force Ones were. He just had a killer North American t-shirt that somehow ended up in India, like a lot of clothes. Western clothing brands get recontextualized there in a way I really like. Once I saw a woman on the Delhi subway with a bag bearing Prada and Gucci labels.

Anyway I loved Ajmer and was quite in awe. We went to a famous, beautiful mosque. You feel the hum that comes with being in an old, sacred place where people do today what they’ve done for many years.

You don’t always need a detailed history of what you’re looking at it to feel this hum. I’m not excusing ignorance, just you’ll never understand everything when you travel, and succumbing to the pressure of trying to is futile. I’ve learned to just enjoy it without needing a tour guide type of explanation for it all. The musicians in the mosque playing the harmonium and percussions were really cool.

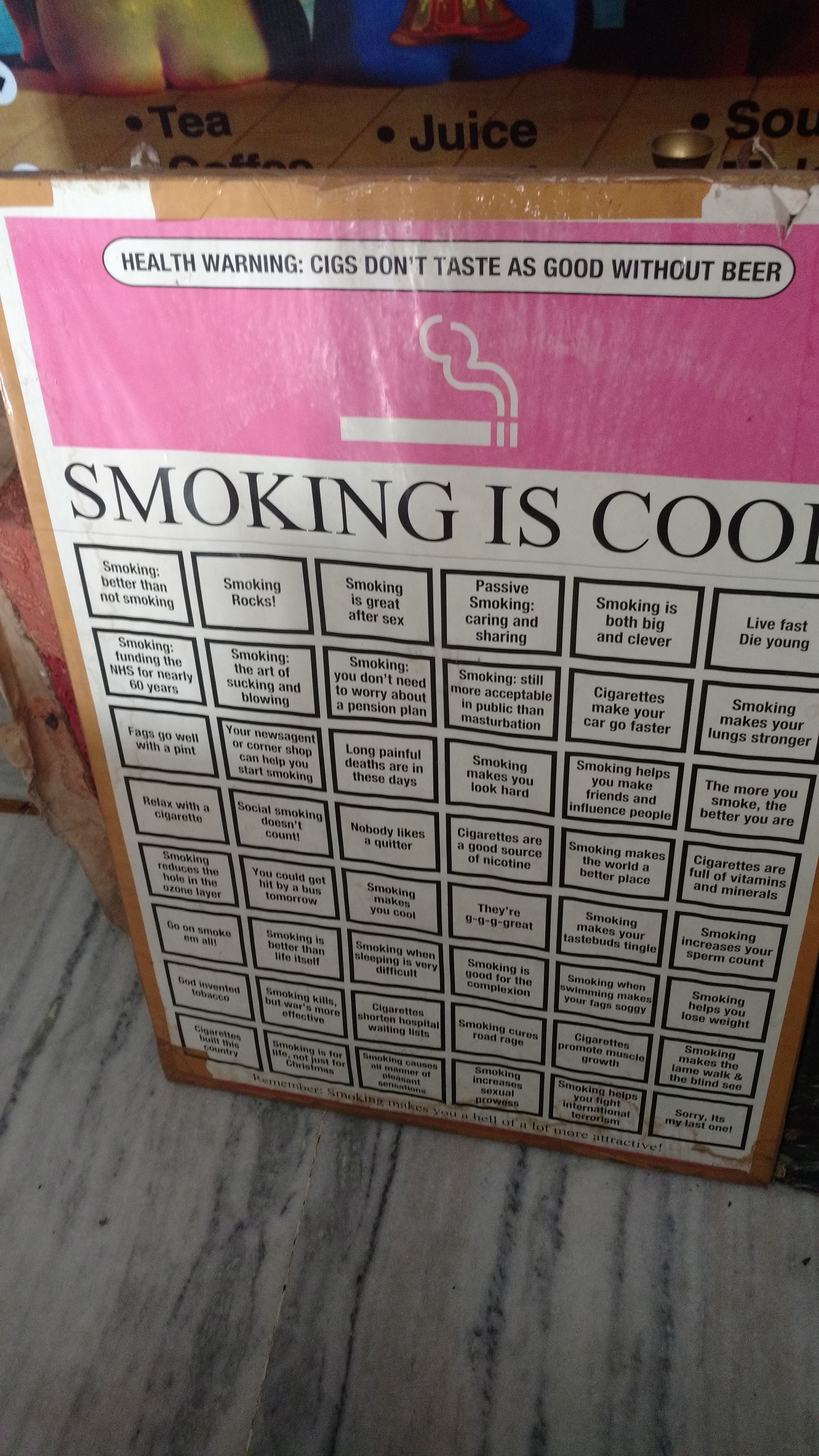

We got to Pushkar later that day and stayed at the Pink Floyd hotel. It was a rock and roll themed place with none of Delhi’s buttoned-up culture. Things were loose, very loose. I explained to the proprietor that because of demonetization, I didn’t have much cash, but I was on the lookout for more. “No problem,” he replied, “we’ve got lots of hash here, man.” That was like the one time in my life that really wasn’t what I meant.

We checked out the famous lake with god men and babas around. Just walking around there was like a miracle. So invigorating and stimulating. The markets were bustling, but there was also a real calm. The calm wasn’t entirely healthy: demonetization had put a damper on things. There were fewer camel merchants and business in general was slower than usual.

You see things that you just don’t see here. I probably saw 100 things that day that all seemed unforgettable, and they merge together and now I feel the impression they made, even if the particulars are foggy. But going to rooftop cafes for a cold beer, some nice food, and incredible views in every direction was great.

The next day we went on a brief camel ride through the nearby desert dunes. I had never been on a camel, and the clothing these camels wore was truly incredible. Vibrant and bold funky ass camels, cooler than that 90s rare gear copper! Gopika and I were having a really good time, just talking and stuff. If there was anywhere to get your mind off the rest of the world, it was here.

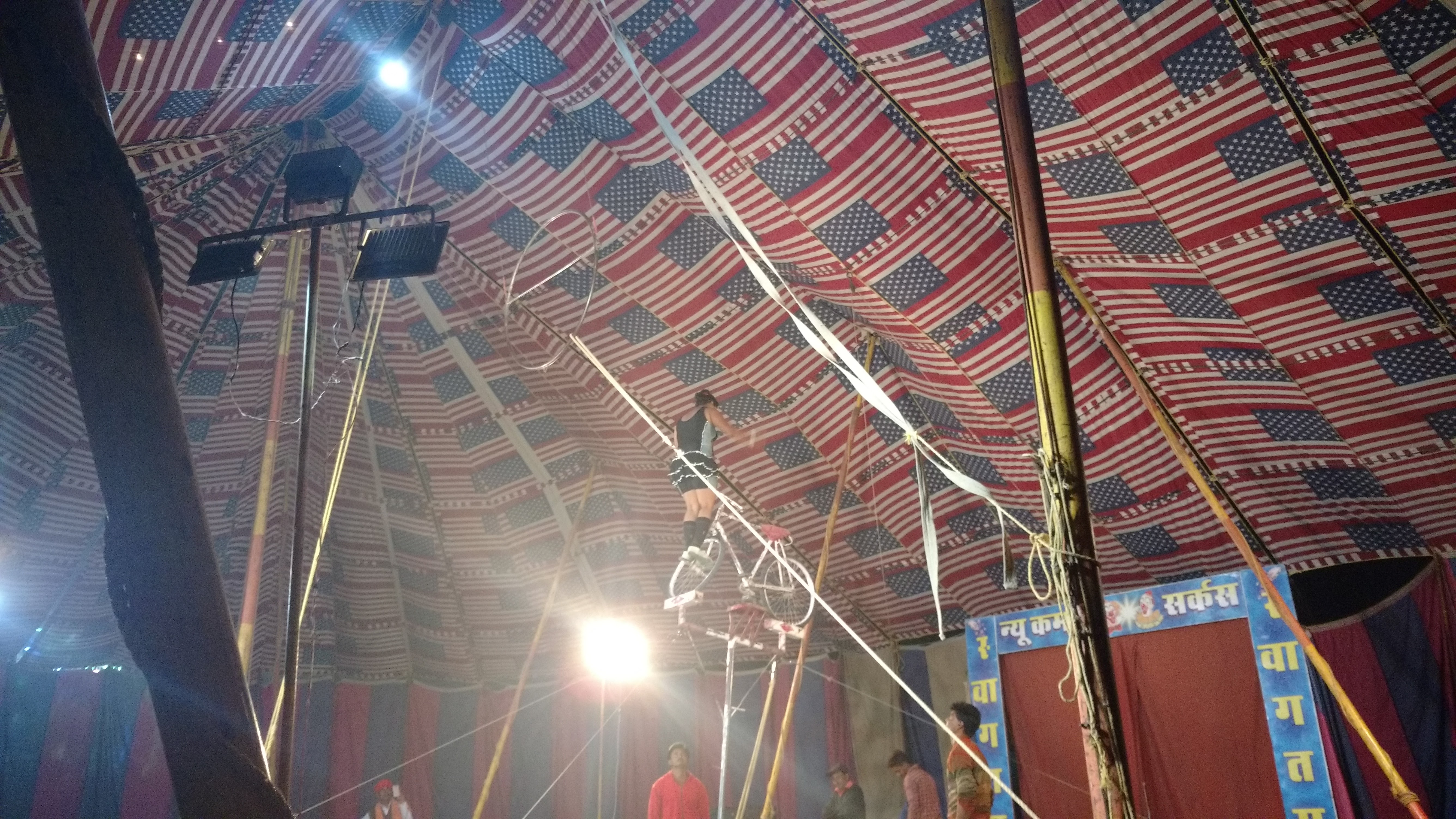

A carnival was in town with the Camel Fair. People selling wares, young girls tight-rope walking with bowls on their heads, that sort of thing. We went on a cool Ferris wheel. We smoked some hash and watched a really exuberant, short gentleman outside the circus tent dance and hype everybody up. Inside the tent was a sketchy, eyebrow raising performance.

You know those old roller coasters that aren’t particularly big or fast, but they’re scary because they’re old and rickety and may collapse at any second? That was the vibe of these daredevil carnies. Juggling fire was fine, but they balanced on bikes high up on small supports and did other jaw-dropping stunts without a net.

The scariest thing was the finale, a man throwing knives at either side of a blind-folded woman’s face, into a wooden board behind her. That cool thing where the knives whoosh and spin and become embedded in their targets mostly didn’t happen. Instead they hit with a clunk and fell to the floor. It didn’t inspire confidence and I was so relieved for that woman when it was over.

In a metaphor extremely on the nose, that threw in my face what I tried to forget, the roof of this crazy circus comprised entirely of upside down US flags. Honestly, what are the odds? The Pushkar Camel Fair circus may have been a bit dubious here and there, but it was America that was upside down.

That day in the market we had ran into a couple friends of mine from WION, Nagen and Ashish. Small world! They weren’t just work colleagues, they were with me in the early days before the station launched, and we’d go for beers together and hang outside work. They made documentaries and TV programs for WION. They both loved to laugh and had a good artistic and political bent. Great people to talk to and it was really nice to see them. It’s funny to think that if I hadn’t come all that way with Gopika, I still might not’ve been alone in the end.

Next day upon leaving, the hotel POS terminal was down. I tried to wire money to pay for our room but couldn’t online bank through my phone. Nobody had cash, the story across the country. I explained the situation to the gentleman and promised I’d pay him when I returned to Delhi, when I had my laptop and bank login info. Thankfully, after a while, he trusted me and that’s what I did.

Sunday night, we took an overnight bus back to Delhi and I returned in time for my Monday afternoon shift without missing a beat. True, Trump was slated to be president and Indians across the country were up in arms about demonetization, but the acute, crushing doom the immediate aftermath of that night was somewhat softened. Thankfully, instead of overwhelming me, it’s slowly rotted my brain every day since for the last decade.

As for demonetization, the uproar from different segments of Indian society was in stark contrast to my station’s all but official position: WION released a shameful TV commercial praising demonetization so gushingly, it would have been an embarrassing thing for the government to release, never mind a news station that was supposed to report objectively.

But then again, Zee Media had an ATM machine inside the security gates that only people with a media pass could withdraw cash from. Once when it was empty, I lined up for cash at an ATM near the office, open to the public, and the picture was very different. I waited for maybe two or three hours, and when the guy finally came to load it up with money, the pushing was real. Nobody got crushed, it wasn’t a herd, but it couldn’t have been easy for women, seniors, or infirm people.

Demonetization continued to ravage India and my privilege didn’t end. It got comically worse.

Second Escape: Himachal Pradesh–Malana, Challal, Kesol

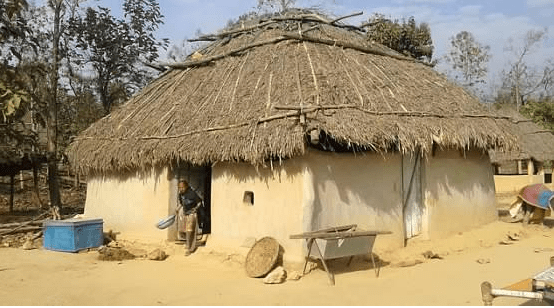

The next week or so, I went on another trip with three good friends (Kandarp, Laden, Varnika, miss you all!) to the breathtaking Parvati Valley in Himachal Pradesh. To Kesol, Challal, and Malana, the latter a small remote village where the inhabitants believe they descend from Alexander the Great and don’t consider themselves Indians, really. They avoid touching any outsider, not even to exchange money, whether from India or anywhere else, not just with white people.

I was told their justice system works as follows: if two people have a dispute, the judge will instruct them to each poison their goat, and whoever’s dies first is in the wrong. To me, this is a smart way of avoiding litigation altogether; it’s a coin toss and your goat will die regardless, so figure it out on your own and don’t burden the courts.

Malana also just so happens to be home to world-class hash. I was told the Italian mafia imports it. For a time, Malana Cream was Amsterdam’s most expensive hash. Children rub the plants in “rubbing season” because their hands are smooth and don’t have lines or creases yet, which isn’t an excuse for child labour, I’m just reporting how it goes there.

Before departing for that trip, I went to a bank in Connaught Place to get more cash than the 2,000 rupee limit ATMs could dispense. The lineup was enormous and wasn’t moving. I had a bus to catch and after a couple hours of waiting I doubted I’d make it. People there needed cash for real problems. This was mine.

Somehow, a bank manager saw me waiting, literally the only white person in line. He asked if I had an ICICI account. I said yes, then he personally escorted me ahead of everybody and two minutes later I left the bank with all the cash I needed. I walked past people sheepishly, apology written all over my face. I didn’t ask for this treatment, but I wasn’t going to say no. Would you have, in my position? And the strange thing was, nobody was remotely upset: The same attitude that told the manager to let me skip the line also made everybody waiting there resigned to it. At the very least, they didn’t seem like they wanted to kill me.

The overnight bus drops you off at 7am for a two or three hour trek up a mountain to Malana. The Rockies and the Alps are pebbles compared to the Himalayas. On a mountain path I saw a sheppard guide maybe 200 of the wildest animals I’ve ever seen, no two coats or sets of horns alike. That trip was truly wonderful too.

Demonetization didn’t accomplish any of its stated aims, which, again, kept changing weekly. There were a few reports of people who misunderstood the news when it broke, and, fearing their life savings suddenly vanished, they killed themselves.

I don’t mean to make light of the enormous problems demonetization needlessly caused. I’m just contrasting my experience with other people’s as much to shine a light on what they went through as what I did. The real point is the discrepency. I suspect the people who pushed demonetization had an even easier time than I did. The thing about privilege is that I never had to lay my claim to it. It was just there, waiting and ready. If you need to assert it, you don’t have it.

I still think demonetization was all a sham and a cover to shock a coveted cash-reliant market at gunpoint into transitioning to a digital economy and digital banking. Whatever benefits from online banking were offset by the many drawbacks and the acute crises people suffered. There were major protests and lawsuits. But soon enough, I’d see vegetable wallahs in Delhi with signs on their carts advertising that they accepted Paytm. Indians are an incredibly resourceful, adaptable, ingenious people.

10 years later, it’s Trump’s second term and he’s threatening to invade Canada, waging economic warfare against us and traditional Western allies, and even deploying his secret police force to attack Americans in Democratic cities. While life goes on and all things do pass, eventually, you need to face reality and can’t keep running away to the desert or the mountains forever.